The Ancestors Of George & Hazel Mullins

by Philip Mullins

Chapter 11 - The War for Confederate Independence

1860-1865

Summary: The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 led to the secession of the

Southern states and war between the United States and the Confederate States.

Almost all white males of military age in Pike County served in the Confederate

armies. The sons of George Simmons and the grandsons of James Hope enlisted

in various local militia units. Some of them were killed and others wounded.

Conditions in Pike County deteriorated after 1862. Beginning in 1863 Union

troops raided in Pike County and in nearby southeast Mississippi civil government

collapsed. The war ended in defeat for the Confederate States.

The election of 1860 leads to secession

The election campaign for US President in 1860 was divisive. The slavery issue

had become a political football by 1852 and its importance increased with every

national election. The 1860 elections were dominated by the debate about whether

or not slavery should be allowed outside of the old South. There were four candidates

on the ballot. On one extreme was Abraham

Lincoln, the Republican candidate, running solidly opposed to any extension

of slavery. He had the support of the abolitionists. On the other extreme was

John C. Breckinridge, the candidate of the Southern Democrats. They wanted slavery

extended to the new territories. In the middle was Stephen A. Douglas, supporting

local self-determination of the slavery issue, and John Bell, urging compromise.

History books often phrase the differences between the candidates in other words.

Some historians prefer to say that Abraham Lincoln was a strong unionist, Stephen

A. Douglas was a radical states-rights man, John Bell a moderate unionist and

John C. Breckenridge a moderate states-rights man.

The issue of slavery became bound up with differing interpretations of the role

of government in a nation that was undergoing a change from an agrarian to an

industrial society. Regardless of how the issue was phrased, the important thing

was that, for the first time since its foundation, the United States of America

had come upon an issue that could not be solved by compromise. The nation had

been held together since its creation by a series of famous compromises fashioned

in Congress by the nation's most famous and respected men. In 1860 the belief

that any difficulty could be overcome by a compromise solution disappeared and

extremists seized control of the US government. Once an impasse had been reached

in Congress, the nation turned to the President for leadership and for the next

16 years the nation suffered the consequences of the decision.

In the election of 1860 the state of Mississippi gave Breckinridge 40,797

votes, Bell 25,040 and Douglas 2,283. Lincoln received almost no votes in Mississippi.

George Simmons,

an uncle of Solomon Simmons, is the only member of the family whose voting record

is known to me. He voted for John Bell, a unionist who urged moderation and

compromise. Like George Simmons many voters in Mississippi voted for moderation

and national unity. Unfortunately, the majority of the country's voters did

not. Nationwide Abe Lincoln won the election with less than one-third of the

votes cast. Stephen A. Douglas ran second. An extremist carried the day and

the stage was set for the secession of the Southern states.

The mood in Mississippi changed after the election of Lincoln. Most Southerners

felt that Lincoln was a radical abolitionist and a tool of eastern business

interests. South Carolina, which had been threatening secession since 1828,

promptly did so. In response the governor of Mississippi called a convention

of delegates from each county to consider whether or not Mississippi should

follow South Carolina out of the Union. The Secession Convention showed that

the white population was unequally divided into two camps. The minority group

consisted of the older and wealthier planters in alliance with the poor non-slave

owning "yeomen" farmers. These non-slave owning whites were from the

Piney Woods

region east of Pike County and from the extreme northeastern corner of the state,

a region known as the Tennessee Hills. This unlikely and unstable alliance of

extreme wealth and extreme poverty was opposed by the large middle group of

white slave-owning farmers living in the old Natchez District, the Central Hills

and the Black Prairie region in the north of the state.

Because of this division the secession convention acted hesitantly at first.

Strong and influential voices speaking for national unity were heard and, at

first, heeded. But the convention dragged on and finally in a burst of enthusiasm

the delegates adopted an ordinance of secession with a vote of 84 to 15 opposed.

The convention went on to proclaim Jefferson Davis Major-General of the State

troops and to adopt the Bonnie Blue Flag as the new State flag.

They called upon the remaining southern states to join Mississippi in a new

confederacy to be closely modeled after the Union they had just left.

The secession of Mississippi and the Civil War that followed had been a long

time coming.

There were many reasons why the disagreements between the north and the south

finally led to the dissolution of the union. The secession of the southern states

was not caused solely by slavery or by the tariff or by the troubles in Kansas

or Cuba. It was not caused solely by disagreements in Congress and the Supreme

Court over interpretation of the Constitution or questions of state's rights.

It was not caused solely by Abe Lincoln or by the nullifiers or by the price

of cotton. Nor was its sole cause the long-standing dispute over control of

the northwest or of what we would now call agricultural and industrial policy.

The truth is that each of these problems contributed to making secession a possibility.

Each of these problems became a rallying cry which was used to justify and expand

the secession movement once it had begun. From the point of view of the small

farmers in Mississippi, the war itself came about because the United States

Army invaded Virginia in an effort to force "the sovereign and free state

of Mississippi" to remain in the union against the expressed will of its

people. Whatever resistance there had been to secession, and there had been

plenty, largely disappeared when the Union army invaded Virginia. Lincoln's

show of force in northern Virginia only worsened an already dangerous confrontation.

The invasion of the South

The first invasion of Virginia by the US Army in 1861 and its subsequent defeat

galvanized the people of the South.

Almost to a man Mississippians responded to the state government's call to arms.

To the white people of Mississippi the struggle of the Confederate States of

America against the United States of America became a continuation of the struggles

their grandfathers had waged against the British between 1776 and 1793 and again

from 1812 until 1815.

The people of the northern states and some of the allies of the Confederate

States saw the struggle in an entirely different light. They increasingly considered

the struggle to be a war against slavery.

The fact of slavery became more important as the war wore on. Its existence

was exploited by the federal government to weaken the South and to gain support

for the war in the north. By portraying the war as a crusade against slavery

the federal government also quieted many of its own domestic critics and weakened

support for the Southern cause in Great Britain.

The Emancipation Proclamation

, declaring all slaves in the Confederate States to be free, was not issued

until January 1863. Its primary purpose was to gain the support of the southern

Negroes for the Union army. Prior to 1863 many slaves had been unwilling to

cooperate with Yankee troops. Their experience was that the Union troops "raped

and stole from the blacks at every opportunity". Some slaves had even volunteered

for military service with the Confederate States Army. However as soon as the

blacks learned about the Emancipation Proclamation, almost all slaves became

pro-Union. The South could have regained their active support only by emancipating

them all immediately. This the Confederate leaders would not do. As a military

move the Emancipation Proclamation was a masterful stroke. Its long-term consequences

were a disaster for the South and for the American Negroes who lived there.

Federal authorities recruited black soldiers in the border states, which were

not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation, with the promise that their families

would be freed in exchange for military service. This enlistment incentive and

post-war legislation caused slavery to disappear in those states. The Confederate

authorities did not make a similar offer to potential recruits among the southern

blacks nor did they ever offer to free all slaves with or without conditions.

Without such an inducement the younger slaves remained neutral or escaped to

the Union side at the first opportunity.

Sometime their resistance took more active forms. After learning about the Emancipation

Proclamation, some slaves in Lafayette County, Mississippi, drove the plantation

overseers off the farms and divided the land and farm implements among themselves.

In Yazoo City slaves burned the courthouse and a dozen homes in 1864. In northern

Louisiana after the arrival of federal troops slaves sacked some of the plantations.

Whatever the original causes of the Civil War may have been for the Negroes

it had become a chance to end the curse of slavery.

None of this could be foreseen in the early days of the Confederacy. Defeat

was not discussed and public support for the secessionists was riding high all

over the South, in some cities in the north and overseas in Great Britain. In

January 1861 Mississippi became the second state to join the Confederate States

of America. The state's favorite son, Jefferson Davis, became the first and

only president of the Confederate States.

Jeff Davis was a politician from southwestern Mississippi. He grew up near Woodville,

65 miles west of Pike County. He was a hero of the Mexican War, had been Secretary

of War under US President Pierce and, as a US Senator from Mississippi, announced

his state's withdrawal from the Union on January 21, 1861.

The people of Pike County answer

the call to arms

78,000 men from Mississippi were enlisted or conscripted into the armed forces

of the state and the Confederate States Army.. This is a figure higher than

the number of white males between the ages of 18 and 45 in the 1860 census.

By April 2, 1865 fewer than 20,000 were "present or accounted for."

The rest were wounded, killed, missing, died, taken prisoner or had deserted.

Incomplete records list 5,807 killed, 2,651 wounded, 6,807 died of disease and

11,000 deserted. In Pike County 11 companies of troops were raised consisting

of over 1,000 men out of a total population of 11,135, including 4,693 slaves.

In his book entitled "Bala Chitto Simmons Family," Hansford Simmons

names 18 grandsons of Ann Simmons who served in the military during the War

Between the States. Eight of Ann's grand-daughters married men who are named

by Mr. Simmons as having been soldiers during the War. In the family he knew

best, that of his grandfather George, all six sons and both sons-in-law are

known to have served in the armed forces of the Confederate States.

Of those eight soldiers, one died of wounds, another was wounded and recovered

and a third had lasting health problems as a result of his military service.

In addition the father of the family, George Simmons, died of pneumonia as a

result of a futile attempt to locate a son wounded at the battle of Shiloh.

Of the 26 men known by Hansford Simmons to have served in the Confederate armed

services, four died of wounds or illness, four others were wounded but fully

recovered, two suffered lasting health problems and one lost an arm.

Another group of which I have information are the children of four of the

eight daughters of James and Isabelle Hope.

Three of these sisters married Simmons brothers and a fourth married Isham Varnado,

a son of Leonard Varnado.

At the start of the war Isham and Margaret Varnado had six sons who were 14

or older. All six served in the military in some capacity, two were killed and

two others wounded. Margaret's older sister, Barcenia Simmons, had three sons

of military age. All three served in the military, two were wounded and one

of those lost part of an arm. The third sister, Mary Simmons, had four sons.

Two are known to have been in the military and one of them died of illness while

in mklitary service. Two of Mary's four sons-in-law are also known to have been

in the Confederate army.

The eldest daughter of James and Isabelle Hope, Nancy, married William Simmons.

They had six daughters and two sons, Solomon and Cyrus. Solomon

was lame from his childhood but is said to have serve as a soldier in some capacity,

perhaps in the Home Guard. A man by that name appears on the rolls of Co. C,

3rd Louisiana Cavalry. Solomon's younger brother, Cyrus, was 19 or 20 when the

war started. The supplement to the Bala Chitto Simmons Family book has a reprint

of a document commissioning a C. S. Simmons as a First Lieutenant in a company

from Pike County. If this refers to Cyrus S. Simmons, then of the 15 sons of

the four oldest daughters of James Hope, we have knowledge that 13 served as

soldiers at some time and in some capacity. The other two may have served as

well but I have no information one way or the other about them.

Of the five families I have examined virtually all of the men of military

age served in the army of the Confederate States.

The youngest sons of George Simmons and of Isham Varnado were too young to serve

in either the regular army or a militia. They were assigned to the Home Guard

in Osyka along with their fathers and other men who were either too old or otherwise

exempt from the regular army. Not all of the men in the army actually left Pike

County. Some of the militia and the home guard stayed at home. Some of the active

duty men were stationed nearby at Port Hudson on the Mississippi River or at

Camp Moore on the railroad just south of Osyka.

Others were attached to the Army of the Tennessee. A small group of men fought

all of the war in Virginia. Notable among these were the Quitman Guards.

Of the Simmons and Varnado men we have mentioned, four, all of them brothers,

joined Rhodes Cavalry when it was organized in Osyka in 1862. Two others joined

the Beaver Creek Rifles and became a part of Wingfield's army at Port Hudson.

Another joined Nash's Company when it was organized at Magnolia in April 1862.

Nash's company became part of the 39th Mississippi Regiment, Army of the Tennessee.

Reddick Simmons, a son of George Simmons

and Mary Ann Sibley, joined the McNair Rifles of Summit along with 115 other

men. This company left Summit in November 1861 for New Orleans via Natchez.

It eventually became Company E, 45th Mississippi Regiment, 3rd Battalion, Army

of the Tennessee. Reddick was wounded at the battle of Shiloh in southwestern

Tennessee in April, 1862. His father traveled to Corinth, Mississippi, in an

unsuccessful attempt to locate Reddick. George Simmons traveled on open flat-cars

part of the way and caught a cold that developed into pneumonia. He returned

home but did not recover. He died April 25, 1862. His son recovered from his

wounds and survived the war.

A nephew of George Simmons likewise died of what we now consider a curable

illness. William E. Simmons enlisted in the 3rd Louisiana Cavalry in the spring

of 1862. This was a part of Wingfield's army but was stationed at Camp Moore

just across the state line in Louisiana. During the summer his father learned

that William was seriously ill. He fetched William from Camp Moore and left

him in the care of William's in-laws.

By September William had died. He was 18 years old.

The Quitman Guards included five of Ann Simmon's grandsons. Four were enrolled

as privates and one as a sergeant. There were originally 107 men in the unit.

George Simmons Jr. was the first to join. His brother Jeff followed soon afterward.

George Simmons Jr. was already enrolled when the company was mustered into state

service at a public ceremony at the Pike County Courthouse in Holmesville on

April 21, 1861. This was barely four months after Mississippi had seceded from

the Union. The Quitman Guards were the first and the most famous of the fighting

units organized in Pike County. It had been organized as a small honorary militia

unit in 1859 with 20 or 30 members. The name of the unit honored a former governor

of Mississippi who was a hero of the battle of Chapultepec in the Mexican War.

By 1858 Quitman was a representative in the US Congress. The Quitman Guards

had fancy uniforms and were popular with the patriotic ladies. On July 4, 1860

at the annual barbecue and rally, the ladies of Holmesville presented the Guards

with a banner costing some $250 as a symbol of their esteem.

When the war broke out the Quitman Guards were reorganized as a militia company

of about 100 men.

It was the only company in Pike County to respond to the first call by state

officials for a mustering of militia in Holmesville. Large crowds had gathered

for the swearing-in ceremony. A week later the scene was repeated in Magnolia

when the young heroes boarded a train for Corinth in northern Mississippi. Both

the soldiers and the crowd were in a jubilant mood. The men had resplendent

new uniforms and their folks were proud if apprehensive. The Quitman Guards

rendezvoused at Corinth with nine other companies, including the Summit Rifles,

to form the 16th Mississippi Regiment. The men elected their officers and enlisted

for a period of one year beginning May 21, 1861. They trained at Corinth until

news came from Virginia of the first battle of Manassas or Bull Run in July.

This was the first large battle of the war and was a victory for the Confederates.

The 16th Mississippi Regiment was ordered to Virginia to become part of the

Army of Virginia. By the spring of 1862 the Quitman Guards found themselves

north of Richmond and in the thick of the action. Shortly after defeating a

force of 20,000 Federal troops under General Banks in the Shenandoah Valley,

Stonewall Jackson's foot cavalry, of which the Quitman Guards were a part, crossed

the Blue Ridge Mountains just in time to attack the right flank of the Federal

army at Mechanicsville on June 26. This forced the Union troops to retreat to

Cold Harbor during the night. There the Federal troops entrenched themselves

on a hill with a ravine in their front. The next morning the 16th Mississippi

charged through the ravine and forced the Federal troops to retreat again. In

the course of this attack about 80 men of the 16th Mississippi Regiment were

killed or wounded including George Simmons. He was shot in the foot. At this

point the two brothers, George and Jeff, became separated. George went to a

hospital near Richmond while Jeff went with the Quitman Guards in pursuit of

the Federal troops in what is known as the Battle of Seven Days. Jeff never

saw his brother again.

Some years later one of Jeff's brothers-in-law met a doctor who had been attached

to a hospital near Richmond during the war. The doctor related that a soldier

named George B. Simmons was brought into the hospital with a wound in his foot.

The wound was infected. The doctors wanted to amputate the foot but the soldier

refused, probably thinking that he would pull through after all. Having refused

treatment, he died three weeks after he was wounded. He was 23 years old.

Two months after the death of George Simmons, his cousin's husband Reeves

Rhodes, also with the Quitman Guards, was wounded at Sharpsburg, Maryland. Two

years later another cousin, Hansford Sandifer, was wounded and later captured

during fighting at the Spotsylvania Courthouse near Richmond. The Quitman Guards,

now known as Company E, 16th Mississippi Regiment, stayed in northern Virginia

for the remainder of the war. Jeff Simmons stayed with the company until the

end. His experience as a part of Stonewall Jackson's foot cavalry affected his

feet and he had foot problems for the rest of his life.

The war in Pike County and surrounding

areas

Meanwhile back in Pike County, the people were also feeling the effects of

the war. The young women and their children moved in with parents or parents-in-law

and families living in Osyka or along major roads moved back to the more isolated

farms. Elderly men, young boys and women took charge of the slaves and did the

farming. Because the state government could only supply its troops with the

basic necessities, it fell upon the folks at home to supply extra equipment

if they were able. The women, as always, spent much of their time making clothing

for their families as well as their husbands and relatives in the military.

Now all cloth had to be made at home as well. This was a long and laborious

process that the younger women had to learn from their mothers or grandmothers.

Spinning wheels and looms that had been relegated to attics and storage sheds

for a generation were repaired and put to use.

In the first year of the war Federal naval forces seized all major forts and

cities on the Atlantic coast except for Savannah, Georgia; Charleston, South

Carolina and Wilmington, North Carolina.

In 1862 New Orleans and Pensacola, Florida, were occupied by Union troops.

The US Navy prevented neutral ships from entering to pick-up or discharge cargo.

Only the occasional ship was able to escape from the blockaded ports and fewer

still were able to return with supplies from England. The embargo created shortages,

often acute, of everything from needles to salt. Pioneer skills still remembered

by the older people became important once again. The Confederate and state governments

made great efforts to overcome the lack of manufactured goods. Efforts were

made to concentrate industry in Mississippi because it was considered to be

a safe area.

Tents, uniforms, hats and blankets were made in factories in Jackson, Natchez

and other Mississippi towns. The cloth from the mills at Jackson or Wesson was

cut at the factory and then taken to soldier's wives in the countryside to be

sown. The Cadis Iron Foundry in Osyka produced cannon barrels. The barrels were

hauled by wagon to a railroad in Clinton and then shipped by rail to Port Hudson

on the Mississippi River where they were mounted. One of the largest tanneries

in the Confederacy was in Magnolia.

It processed 600 hides a day. Because of this tannery at Magnolia it is likely

that Pike County became a center for the manufacture of boots and shoes., The

military store in Osyka had some 100 dozen pairs of boots and shoes when the

Federal troops burned it in 1863. These may have been made locally. Solomon

Simmons

may have made shoes during the war since he left a number of homemade shoes

of his own manufacture in the attic of his home near Emerald.

A hospital in Magnolia cared for soldiers from all over the region. The Confederate

Cemetery in Magnolia contains the graves of over 70 men who died at the hospital

during the war. Military stores were set up at Summit, Magnolia and Osyka to

purchase and warehouse products useful to the army.

However two years after the secession of the state, Pike County could no longer

boast that it was secure from the enemy. The warehouses became the targets of

Federal raiding parties.

In April 1862 the Federal army and navy captured the

city of New Orleans.

The Yankees made no immediate attempt

to move northward up the railroad. Instead they concentrated their efforts on

reestablishing control of the gulf forts and the Mississippi River. One of the

largest Confederate training camps, Camp Moore, was located on the New Orleans,

Jackson and Great Northern Railroad one mile south of Tangipahoa, Louisiana.

This prevented Union troops from moving into Mississippi from New Orleans.

To prevent the Yankees from moving up the Mississippi River, Port Hudson and

Vicksburg, some 140 miles further up the river, were heavily fortified. Port

Hudson

is a small town upstream of Baton Rouge. Vicksburg and Port Hudson became the

last Confederate strong points on the Mississippi River. At Port Hudson the

military built breastworks that extended for four miles and an army under the

command of General Wingfield was sent to defend it. Several of our cousins were

stationed at Port Hudson. Hansford Simmons recalled that two of his father's

brothers were there in a company called the Beaver Creek Rifles. One of these

men was given a short leave and came home to visit. When the leave was over

a younger brother, who was only about 14, went back to Port Hudson in his brother's

place. He answered roll call and performed his older brother's duties for about

30 days. Finally the soldier returned from his leave and his child replacement

went back to the farm in Pike County.

Port Hudson was attacked by Union gunboats in the summer of 1863 shortly after

the Union army under General Grant laid siege to Vicksburg. The youngster who

had substituted for his brother was fishing with a companion on the Bala Chitto

Creek on the night the Union gunboats attacked Port Hudson for the first time.

He recalled, "We heard the cannon so plain but we didn't know just where

they were. It was a fair night and we could see the light of the cannon flashes."

This was at a distance of 50 miles. The siege of Port Hudson lasted until July

9, 1863. When it and Vicksburg were captured by Grant's army, Texas and the

other states west of the Mississippi River were completely cut off from the

rest of the Confederacy.

James Bond, a son-in-law of Rebecca Simmons, was killed near Port Hudson at

2 PM on July 15, 1863. By then Federal troops had already captured Port Hudson

and a large part of Wingfield's army. The two Simmons men with the Beaver Creek

Rifles were captured. The Confederate officers were imprisoned but the enlisted

men were paroled and allowed to leave. Most of the men immediately went home.

Others went with their units to Demopolis, Alabama to regroup. Eyewitnesses

recall seeing these soldiers bathing in the Tombigbee River shortly after their

arrival from Port Hudson. Most of them were black and blue on both shoulders

from the recoil of their rifles. So many of the men had deserted that the companies

were disbanded and never reactivated. Some of the men re-enlisted in other commands

but most remained at home "on parole" for the remainder of the war.

Beginning in the spring of 1863 Federal troops periodically passed through

Pike County destroying military stores and stealing food and supplies. After

the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson in 1863 the Confederate Army withdraw

its infantry from Mississippi. Only a few cavalry units were left to harass

Union supply lines and to protect the state. The Union army raided more or less

at will after the fall of 1863. In her book "Osyka", Lucy Varnado

retells several interesting stories about these raids. One of the first and

the most spectacular occurred in April and May of 1863. It is known to historians

as Grierson's Raid.

"On April 30, 1863, General Benjamin Grierson's

forces arrived in Summit. Here they captured or destroyed stores of food, whiskey

and ammunition. The bridges and railroad rails were all destroyed. Captain

Thomas

C. Thodes, with only 30 men, guarded Osyka. He realized the immense value of

the storehouse of military supplies in Osyka. It is said that the Masonic Lodge

called a special meeting and, with the captain, planned a ruse that would save

Magnolia and Osyka. Captain Thodes sent 2nd Lieutenant William S. Wren to spread

the rumor at Summit that Osyka was protected by two regiments of CSA infantry,

one of cavalry and a battery of artillery. Col. Grierson decided to cut across

the pine land via Gillsburg and Greensburg, headed for Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Grierson's decision saved Osyka and Magnolia."

A part of Grierson's force was engaged by the home guard

on the Tickfaw River just east of where Gillsburg, Louisiana, is now. In those

days, the area was known as Oak Grove, as was the plantation belonging to Charles

Wall. When the Yankee troops arrived at Oak Grove, Mr. Wall's son, who was

a

Confederate officer, was at the plantation on furlough while recuperating from

a wound. The following story is quoted from the Pike County Herald of Magnolia

as reprinted in Lucy Wall Varnado's book.

"On this particular occasion young Col. Blackburn

from Illinois was in charge of the regiment that came through this part of

the country to pillage and burn. When they reached Oak Grove, the colonel was

not

with the first part of the regiment which proceeded to ransack and tried to

burn the place. Colonel Blackburn rode up in the meantime and asked Mrs. Wall

if she would serve a meal to him and his staff. She replied she would if he

would restore order to the place, which he quickly did. He also gave orders

as to their line of march, which was over Little Tickfaw and Big Tickfaw, scarcely

a half mile from the house. One of the slaves overheard the command and immediately

conveyed this information to his young master who was in hiding to avoid being

taken prisoner. Captain Wall immediately went down into the dense swamp of

magnolia

and birch trees to where some of the young boys and men too old to go to war

were swimming in Big Tickfaw Creek. They had their guns with them. They went

quickly to Little Tickfaw Creek which the US army had to cross. There they

removed

the planks from the bridge. The men and boys then climbed into the tops of

the trees and waited.

"Soon the regiment appeared and, of course, could

not get their equipment across the bridge. The colonel sent a dozen men over

and they were immediately fired upon from the tree tops. The Yankees had no

idea how many Confederates were concealed in the swamps so they repaired the

bridge as quickly as possible and got away taking their wounded but leaving

their dead.

"After they got across the Big Tickfaw bridge, they

found their Colonel Blackburn so desperately wounded that they had to leave

him in a house nearby. Mrs. Wall, upon learning of the colonel's plight, sent

for a doctor and took one of the slaves and went to him. He was so desperately

wounded that he could not be moved to her house. She tenderly cared for him

during the several days that he lived. When he passed away, she had him buried

on the nearby hill side where now still rest the seven Yankee soldiers who

were

killed at the bridge. Before Colonel Blackburn passed away, he gave Mrs. Wall

his watch and requested that she give it to anyone coming South in search of

him.

"Years later after the war ended, Mr. and Mrs. Charlie

J. Wall went to New Orleans. On their return trip while on the train they noticed

a young man and became engaged in conversation. He told them that he was going

to Osyka in search of the body of his uncle, Col. Blackburn, who was killed

during the war. Mr. and Mrs. Wall were very happy to give him the information

he wanted, taking young Blackburn home with them for the night.

"Next morning Mr. Wall with several Negro slaves

who had remained with him took wagons and mules and exhumed the body. The young

man had even brought a coffin with him. The Negroes drove him to Osyka for

the

train; with tears in his eyes he thanked Mr. and Mrs. Wall for their kind deed.

She, in turn, gave him the colonel's watch which was being carried back to

his

wife."

The war ends in defeat

In the fall of 1863 Federal troops were again in the area. This time they

burned Camp Moore and destroyed the supply depot in Osyka.

In addition to the 100 dozen pairs of boots and shoes, the warehouse contained

4,000 pounds of bacon, 12 barrels of whiskey and large quantities of corn and

corn meal.

Lucy Varnado tells this story in her book. "Parham Boyd Varnado, born in

1852 the son of Isham and Margaret Hope Varnado, often related this story of

the Civil War.

When he was around 12, he remembers the Federal troops passing his father's

plantation. The large army stopped at the home to get water from the large dug

well. It took all day for the army to pass. Parham remembered the exact spot

on the porch where the commanding officer sat. The army carried pontoons for

crossing the rivers where there were no bridges. While Isham and the officer

were talking, they heard pigs squealing. Some of the soldiers had thrown the

pigs into the pontoons, hoping to eat them later. Their commanding officer had

the soldiers return the pigs to the owner. This event must have taken place

in the fall of 1863 since there was much military activity in the Osyka area

at that time."

The raids continued throughout 1864. The minutes of the Mississippi Baptist

Association record that although the annual convention was held as usual in

1864 many churches sent no delegates. The convention was held in a church in

Summit and had to be adjourned sooner than planned because Federal troops were

expected to raid the place in "a few hours."

As early as December 1862 Mississippians had become discouraged by the course

of the war. Defeats in Tennessee and on the Mississippi River demoralized the

troops and desertion and straggling increased. The draft law proved to be impossible

to enforce and soldiers who had been captured and then paroled were allowed

to stay home if they wished. In 1863 conditions worsened. In the spring Colonel

Grierson's three mounted regiments traveled from Memphis to Baton Rouge right

down the middle of the state without meeting any serious resistance.

On July 4, 1863 Vicksburg surrendered. On the 9th, Port Hudson followed.

Both paroled armies, consisting mostly of local men, disintegrated. On the same

day that Port Hudson surrendered the state capital at Jackson was burned by

Federal troops. The state government fled Jackson for smaller towns to the east.

After July 1863 civil law in Mississippi came to an end. Military guards were

stationed in towns but farmers were forced to band together to protect their

crops from marauders. These men, also called jayhawkers, were particularly common

in southeastern Mississippi. Families moved away from the main roads if possible

and the remaining livestock was hidden away.

The slaves in general stayed at home and out of trouble. However by the spring

of 1864 there were an estimated 10,000 white deserters in Alabama, Mississippi

and southeastern Louisiana. Military desertion had become so common that in

late 1864, of the 537 men sent to conscription camps in Mississippi, 302 deserted

before their units left the state.

In Greene, Perry and Jones counties in southeastern Mississippi deserters and

draftees banded together and raided government warehouses. In Jones County these

men, led by Newt Knight, were the de-facto government. They arrested Confederate

soldiers and officials who came into the area and released them with paroles

written on pieces of birch bark because they had no paper. They tried to make

a deal with the Federal army on the Gulf Coast but were rebuffed by the Federal

military commander. In early 1865 the Confederates finally sent troops against

them but Knight and his men either fought the soldiers to a standstill or escaped

into the swamps along the Leaf River. Closer to Pike County, in Covington and

Smith Counties, public unionist meetings were held. The state government responded

by sending troops to arrest the unionist leaders. Although there was no open

resistance to Confederate authority in Pike County, there were reports of disloyalty

in Pike, Copiah, Lawrence and Marion Counties even before the fall of Vicksburg

in 1863. Unionist handbills were posted in Summit and there were reports that

abolitionists were talking to slaves on plantations in the northern part of

the county.

The economic situation grew steadily worse. By January 1864 the Confederate

dollar was selling for two cents US.

By April 1865 the Confederate dollar was worth one and a half US cents. With

Confederate money almost worthless and only a small amount of railroad, bank

and state notes in circulation, the people became dependent on barter. Even

taxes were paid in kind. The people were forbidden by law to sell their cotton

to the Yankees and, since there were few textile mills in the South, the bottom

dropped out of the cotton market. Food was available and 1863 was a good year

for both corn and wheat. Meat was relatively abundant but the salt for preserving

it became scarce after the mine at Avery Island in Louisiana was captured by

the US in 1862. The state built a plant to manufacture salt for the families

of soldiers and other salt was brought in by blockade runners or purchased as

contraband.

By 1863 all manufactured goods were becoming hard to find and it was apparent

that it was impossible to make everything locally. Even the State of Mississippi

was forced to buy contraband goods when it launched a campaign to increase the

production of cloth. The officials in charge found that no one in the South

could supply the cards needed to make thread. In 1863 trade with the Yankees

was still illegal but the legislature made an attempt to legalize what was an

already wide-spread practice. By 1864 the Confederate authorities stopped confiscating

illegal trade goods and the trade with the Union-held town of Vicksburg grew

to enormous proportions. In southwestern Mississippi illegal trade went through

Natchez, Port Hudson, Bayou Sara and the shores of Lake Pontchartrain.

Most of the illegal trade involved selling cotton. It was a dangerous and

high dollar business. It was necessary to deliver the cotton to the buyers without

meeting troops of either army. If the cotton was intercepted it was either burned

by the US army or confiscated by the rebels.

The price of cotton rose steeply after 1862 and the merchants involved in the

trade often amassed considerable fortunes, usually in land or cotton. The small

farmers accused the merchants of profiteering but they desperately needed the

greenback dollars to survive. Their situation became increasingly difficult

with each passing year.

In May 1865 Robert E. Lee found himself in command of the last remaining Confederate

force with offensive capabilities. He bowed to the inevitable and surrounded

his army to US General Grant. On May 8 the Army of Mississippi followed suit.

The governor of Mississippi announced that all Confederate armies east of the

Mississippi River had surrendered. He issued a proclamation urging local authorities

to maintain order and to suspended the collection of taxes. It had taken three

years and three million Union troops to end the war for Confederate independence.

The 600,000 soldiers of the Confederacy had done all they were able to do.

The secession had failed. The war was over. The veterans of the Confederate

armies were quickly paroled and sent home. The prison camps were emptied. The

younger Negroes left the farms and gathered in the towns in anticipation of

the fruits of freedom. The country was defeated and demoralized. Confederate

currency was worthless, mills and machines destroyed or melted down, railroads

torn up, bridges destroyed, homes burned. Stores and animals had been requisitioned

or stolen, the slaves had been freed without preparation or compensation. Many

of the veterans were disabled either physically or mentally by the war. Many

widows were destitute. It was a time of confusion and poverty for everyone,

black and white. It was a time for reconstruction.

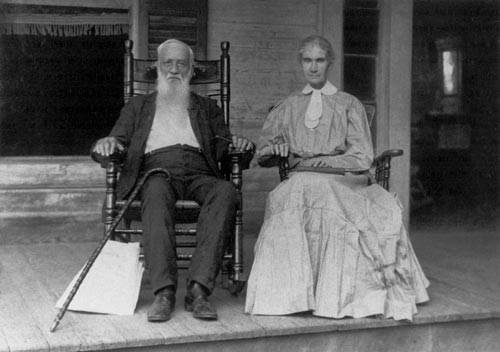

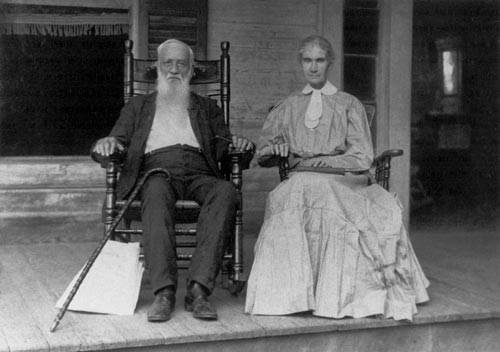

William Mullins and wife (1890)

11-1

|

Back to Table of Contents

| Chapter 12

Copyright © 1994-2005

by Philip

Mullins. Permission is granted to reproduce and transmit contents for not-for-profit

purposes.